Because knowledge mobilization (KMb) is such a complex process, involving many different players and activities, researchers have many different ideas about how it works (or should work). A 2018 scoping review identified 159 theories, models, or frameworks (TMFs, for short), and that number continues to grow each year.[1]

You’ll never learn about or master all of these constructs, and unless you’re doing another scoping review, you don’t need to catalog all of them. It’s helpful, however, to get a sense of the different models available so that when you sit down to develop your KMb strategy or project, you have a sense of the options available to you.

It’s also useful to grasp the basic principles on which the models have been built and the broad trends in the refining of TMFs. That’s what this short article will help you with. It won’t introduce you to every model you’ll encounter in your journey as a knowledge mobilizer, but it will give you a quick overview of how some of the more popular models have evolved. With that basic knowledge, you should be able make sense of any model you come across and decide whether to use it to further your KMb goals.

Four Stages of KMb

We’ll focus on one set of that vast body of TMFs, process models. These attempt to explain how research flows through the so-called research pipeline, how it moves from knowledge creators to knowledge users.

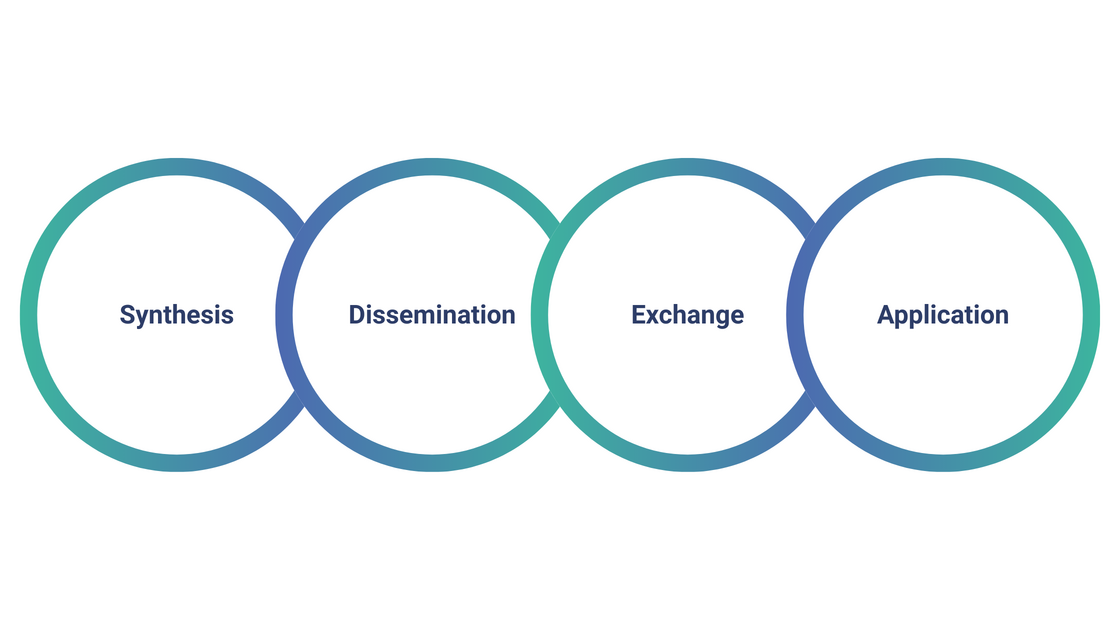

Most of the process models available today come to us from the domain of public health, and many of them derive from guiding principles developed by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR). CIHR was founded in 2000, with a mandate to translate health research into positive health outcomes for Canadians. Early on in that mandate, it identified the following four different categories of KMb activity and presented them in stages, as we see in the diagram below:

Adapted from [2]

Over time, the four stages evolved into what CIHR now calls “the four elements of knowledge translation”:[3]

- Synthesis is the act of pulling together various research findings and integrating them with the existing body of knowledge. This is still really part of the knowledge creation phase.

- Dissemination is the process of identifying the target audience and developing tailored communication products for them.

- Exchange is the two-way flow of information and ideas between knowledge creators (researchers) and practitioners, policy makers, industry partners, or other users.

- Application is the ethical use of knowledge, in compliance with laws, regulations, and social norms.

The conceptual shift from stages to elements reflects the evolution of KMb as a discipline. As researchers learned more about how knowledge moves through people and systems, they bumped up against the limitations of a phased model.

As people experimented with KMb initiatives, they came to realize that thinking of KMb as an intellectual relay race—with knowledge mobilizers passing the baton from one stage to the next—doesn’t acknowledge the complexity of transforming research into impact. Nor does it recognize that the dividing line between “knowledge creators” and “knowledge users” is not always clearcut.

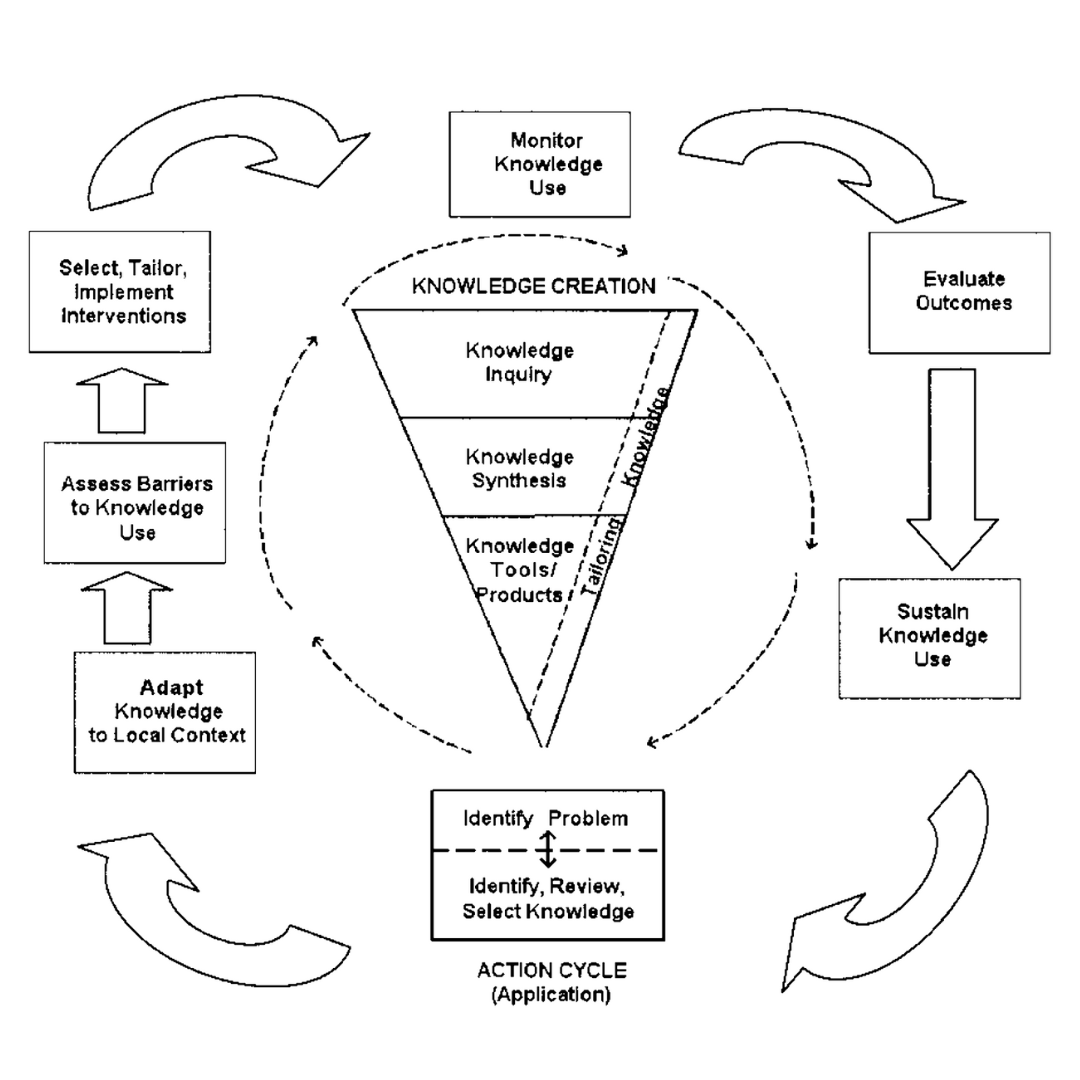

As CIHR’s current website says, “Knowledge Translation is defined as a dynamic and iterative process.”[4] The organization now promotes the popular Knowledge to Action Process model, which depicts KMb as a cycle rather than a linear flow.

Modeling Integrated KMb

Versions of the staged model of KMb still exists, but it mostly finds favor among researchers who produce what CIHR calls “end of grant” KMb. Increasingly, this view of KMb as one-way information-sharing is giving way to “participatory” or “co-creative” models that depict research as a collaborative effort involving knowledge users throughout the process.

As you probably know, Canada’s three major federal funders (NSERC, SSHRC, and CIHR) now require grant applicants to submit a KMb plan, stating how they’ll share their findings outside their traditional, academic audience. The simplest way to do this, especially if you don’t have much experience with KMb, is to tack on a KMb activity to the end of the research project.

This approach assumes that the researcher will complete their study, present the results to their peers through an article or conference presentation, and then repackage those results for a lay audience. For example, they might publish an article in an academic journal and then share a Plain Language summary or infographic on social media. Or they might present their findings at an academic conference and then adapt that to deliver a presentation at their local library.

That model is, however, now starting to give way to the integrated approach. In this methodology, the knowledge creators and the knowledge users work hand-in-glove throughout the research process.

For example, let's say a researcher is doing a study on diabetes in youth. If they’re engaging in integrated KMb, then they would involve the youth from the beginning of the research project. The youth would help design the research questions and methodology. They might be involved in collecting data, and they might help analyze the data and then publish it. They might even be named as co-authors on an academic publication. They would also participate in any knowledge mobilization activities following the study, such as presentations to clinicians or policymakers.

In Canada, one of the most popular models for describing and guiding integrated KMb is the Knowledge to Action framework, which the CIHR now promotes. The diagram below shows this framework as it was first developed by Ian Graham.

[5]

This is a fluid model with permeable boundaries between the different domains of activity. For example, the knowledge creation process includes the production of knowledge tools and products, which falls into the “dissemination” category of CIHR’s four elements of KMb. While knowledge creation and action are represented as two different activities, the starting point (shown in the rectangle at the lower tip of the center triangle) is adaptable. You can begin the KMb process by identifying a problem and then selecting knowledge to apply to it, or you can first choose the knowledge you want to share and then choose a problem related to it.

The Knowledge to Action framework also incorporates evaluation, an aspect of KMb that’s coming under increasing scrutiny. The action cycle includes monitoring, evaluating, and improving the process of KMb on an ongoing basis.

Frameworks from Implementation Science

We have plenty of models describing KMb, and these are impressive from a theoretical vantage point. But how do we know which process will produce measurable results?

That has become the burning question for knowledge mobilizers and funders, and the field of implementation science attempts to answer it. As implementation research comes into its own, it is also producing new TMFs.

Here is a popular model, the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research.

Adapted from [6]

This framework shows five different domains to think about as you move research into implementation. The process flow shows research moving through a range of strategic, relational activities to evolve into a tailored innovation, which is then introduced to the “inner setting” of an organization. That organization is understood in terms of its structure and culture, its surrounding environment (“outer setting”), and the individuals within it.

This model has come a long way from the original four-step model that emerged during the early days of CIHR. It illustrates how multifaceted the process of KMb is and how many variables affect its results.

Allowing for Messiness

Like the other models we’ve considered, the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research doesn’t pretend to serve as a playbook. It presents a way of viewing and understanding KMb rather than a series of steps for executing it.

When you’re on the front lines of knowledge mobilization, models like those we’ve reviewed are most valuable as heuristics, tools for discovery. They provide a high-level perspective of the KMb process, which can save you from getting lost in the day-to-day details and losing track of the goals you want to achieve.

At the same time, when you’re working with a KMb model, it’s critical to recognize that it represents a theory, not lived reality. In theory-world, KMb happens in well-articulated patterns. In your world, you may not find it so easy to map the progress of research from the lab or library into the world beyond your research community.

As we often say at Clarity Connect, “We’re not mobilizing knowledge; we’re mobilizing people.” People make processes messy and unpredictable. Things rarely go exactly according to any diagram.

Some KMb models go further than others in recognizing the people skills needed to turn theory into practice. One of this group is the PARIHS (Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services) framework below.

This framework looks deceptively simple because it has just three domains: evidence, context, and facilitation. But the facilitation piece is in itself complex. The framework assumes, in fact, that users of the PARIHS framework will engage a professional facilitator or facilitators to help mobilize research knowledge. Indeed, each of the three elements in this collaborative model require knowledge mobilizers to engage in deep thinking about and with the intended knowledge users.

More Models to Choose From

Consider this brief overview a taster platter of KMb models. An elaborate menu of other possibilities awaits you if you’d like to investigate the 156+ other options.

If you’d like to explore KMb models further, here are a few frameworks you might want to investigate.

I encourage you to do a little bit of digging and see which of these models resonates with you. Which of these can you see working well with the research that you do and with the community you want to impact?

[1] Strifler et al., (2018). Scoping review identifies significant number of knowledge translation theories, models, and frameworks with limited use. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 100, pp. 92-102. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0895435617314178#:~:text=We%20found%20596%20studies%20reporting,either%20within%20or%20across%20studies.

[2] CIHR. (2016). About Us. CIHR website. https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/29418.html

[3] CIHR is in the process of updating its terminology from “knowledge translation” to “knowledge mobilization.” In this article, the two terms are used interchangeably.

[4] CIHR. (2016). About us. CIHR website. https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/29418.html#2

[5] Graham, I. et al. (2006). Lost in knowledge translation: Time for a map? Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 26: 13-24. https://www.ktpathways.ca/system/files/resources/2019-02/Lost_in_knowledge_translation__Time_for_a_map_.3.pdf

[6] Center for Implementation. (2023). Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. Center for Implementation website. https://thecenterforimplementation.com/toolbox/cfir

[7] Immerzeel et al. (2023). Implementing a care pathway for small and nutritionally at-risk infants under six months of age: A multi-country stakeholder consultation. Maternal and Child Nutrition, 19. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/365383119_Implementing_a_Care_Pathway_for_small_and_nutritionally_at-risk_infants_under_six_months_of_age_A_multi-country_stakeholder_consultation/link/63ea4357eab072152f4349f6/download

[8] Esmail et al. (2020). A scoping review of full-spectrum knowledge translation theories, models, and frameworks. Implementation Science, 15 (11). https://implementationscience.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13012-020-0964-5

Comments